Modeling the missing community-wide effects from the Thibela TB trial

16 Apr 2015Emilia Vynnycky et al. recently came out with an interesting paper in the American Journal of Epidemiology which they try to understand why there were no effects of isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) on community-wide TB incidence in the Thibela trial of IPT among South African gold miners. I thought it would be worth saying something about this for a couple of reasons. First, and least-important, this is a topic that overlaps somewhat with my own work, although in a high-HIV context rather than in comparatively low-HIV Lima, Peru.

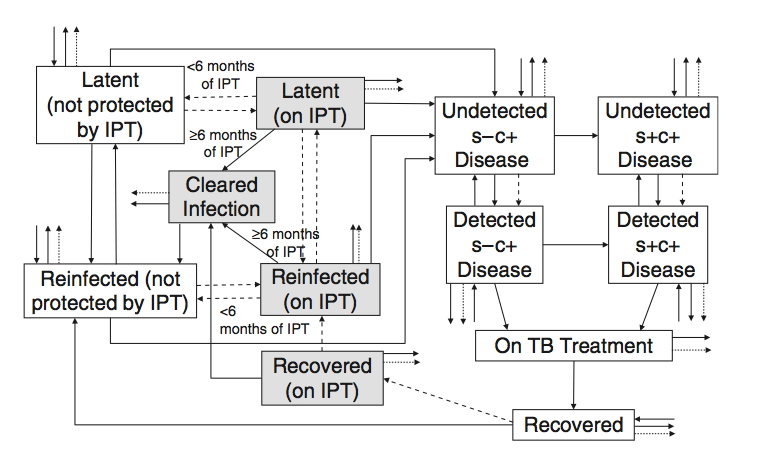

But more than that, this paper is really a great example of infectious disease modeling driven by an important question/puzzle rather than the impetus to model for the sake of it. On a more practical note, it’s also a great example of the pain of modeling TB transmission dynamics. This figure gives you a general sense of the model structure:

We have a lot to keep track of here: smear-positive and smear-negative (s+/s-) individuals who are differentially infectious and die at different rates if not treated, new infections and re-infection events that progress to disease at different rates. And these rates are all different for HIV-negative and HIV-positive individuals. In short, there’s a lot going on.

At the end of the day, there are 41 parameters, most of which are fixed at some value (or set of values) obtained from the literature. The key parameters of interest that they estimate relate to:

-

The ability of IPT to actually clear an individual’s latent TB infection rather than simply suppressing it while the individual is on therapy and allowing it to come roaring back after the patient stops taking isoniazid. And:

-

Protection against reinfection conferred by receiving IPT.

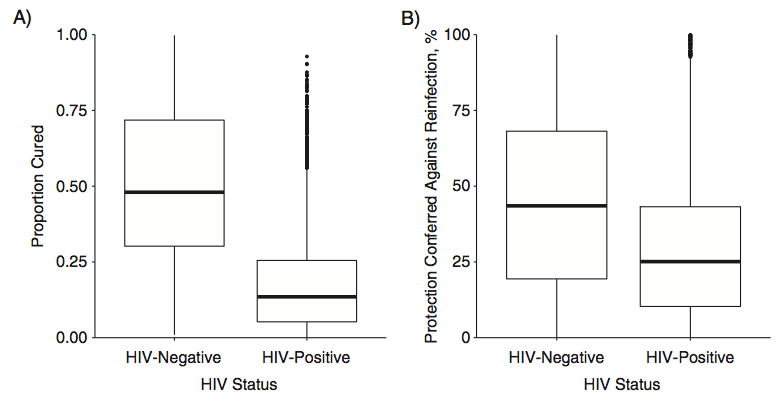

This figure tells the story:

Very few of the HIV-positive miners (who made up the vast majority of TB cases) appeared to have had their infections fully cleared by receiving a course of IPT, and there seemed to be minimal protection against reinfection for HIV-positive individuals as well.

Although these results are not entirely surprising and are disappointing from a policy/programmatic perspective, they do hold out some hope for the potential impacts of IPT on population-level TB rates in comparatively low-HIV/high-TB contexts, like Peru. Although (as the authors point out) the relatively low prevalence of TB among HIV-negative miners means that there is relatively low statistical power for making inferences about effects among HIV-negative individuals.

On top of this, the transmission context is decidedly different here than in a typical community, both from the high prevalence of HIV-positive TB cases (who seem to be less infectious than their HIV-negative counterparts), and also the unique transmission context of a gold mine in which the environment is essentially perfect for facilitating TB transmission.

One last thing that’s worth pointing out here is the way in which they went about fitting the model to the incidence and prevalence data from the trial. The authors used “Bayesian melding,” which is essentially a Sampling-Importance-Resampling scheme in which model parameters are first sampled from a set of prior distributions (informative or otherwise). Parameter sets are then weighted according to the likelihood function (this is the importance step), and resampled according to these weights, to obtain a set of approximate posterior distributions that can be used for inference. One of the advantages of this approach over more traditional MCMC is that it allows you to easily parellelize the most expensive part of the computation, which is the evaluation of the set of differential equations underlying the dynamic model. Beyond this benefit, though, I’m not 100% sure I understand what you get over more classically sequential approaches to MCMC. But this is really more of a question of style (and running time) over substance.