Understanding the etiology of spatial clusters of drug-resistant TB: Clustered social risks, localized transmission, or both?

11 Aug 2015The figure below is from my recent paper on multi-drug resistant TB in Lima, Peru in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, with Ted Cohen at the Yale School of Public Health, Megan Murray, Mercedes Becerra, and others at the Harvard School of Public Health and Partners in Health/Socios en Salud in Lima. This is the latest product of my collaboration with these folks, which has given me the opportunity to explore one of the most interesting datasets I’ve ever gotten my hands on. For other examples of work we’ve done using data from Lima, and a full description of the project see here, and here.

Right now, I just wanted to give a quick plug/preview of our new paper for anyone who is interested.

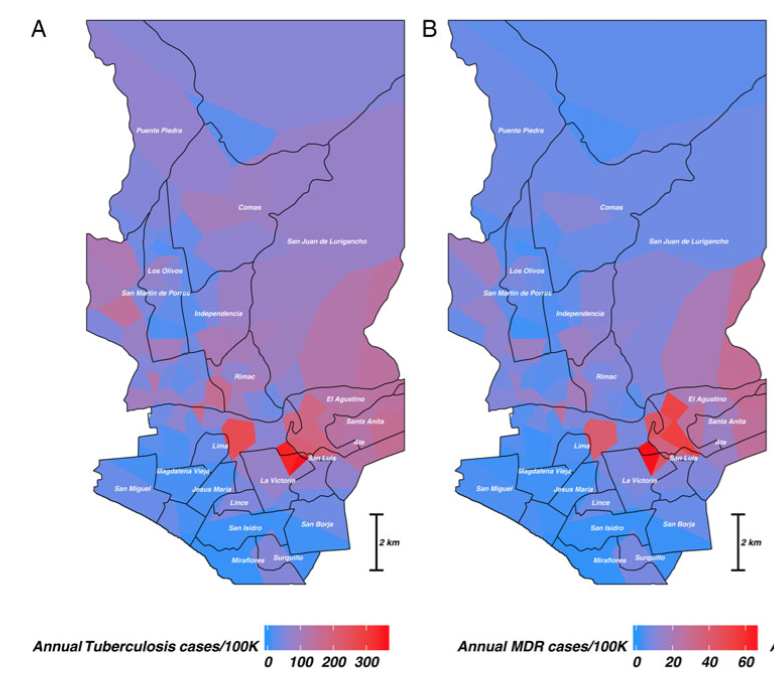

The figure shows (Figure 1 in the paper), is the dramatic heterogeneity in tuberculosis risk by health center catchment (HC) areas of Lima, Peru:

Panel A shows the average annual rate of both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant TB in cases per 100,000 people from 2009-2012. Panel B shows the per-100K rate for just MDR-TB. (These estimates were obtained using Poisson GLM with a Gaussian process smoother using Stan, for more info see the supplementary materials for the JID paper.)

It is not surprising to find groups of TB cases clustered in the same neighborhood or administrative area of a city: the factors that make TB so pernicious tend to reflect local social and economic fractures in addition to regional and national ones. This is particularly true for multi-drug tuberculosis (MDR-TB), as MDR infection may result either from infectious contact with another individiual with MDR-TB, or from incomplete or improper treatment of a drug-sensitive or less-resistant TB strain.

So, one approach we took to figure out whether spatially clustered groups of cases were related was to use distance-based mapping to highlight spatially coherent groups of cases that had not had prior treatment, i.e. they could not have acquired MDR infection as a result of treatment failure. The image below comes from Figure 2B in the paper:

When we did this, we saw a cluster of MDR-TB cases (highlighted in red) that had to have been infected as a result of contact with an MDR case in a portion of Southeastern Lima known as Lima Este. But this spatial clustering could mean that these individuals shared common exposure risks, i.e. they work in crowded factory conditions or public transit, which would give them ample exposure to MDR.

One issue with restricting our focus to just individuals without prior treatment is that individuals with and without MDR may still be linked by transmission, i.e. person A transmits a drug-sensitive infection to person B, who then acquires MDR via treatment failure. When this happens, the social and economic risks that drive treatment failure will be amplified by local conditions that are favorable to TB transmission.

To capture these links and more definitively establish whether these spaital clusters of TB cases reflected transmission, we used each TB case’s genotype, obtained via 24-loci MIRU-VNTR genotyping, to highlight single-genotype clusters using the distance-based mapping algorithm. The MIRU-VNTR genotype uses loci that are unrelated to drug-resistance, so that we can highlight groups of cases linked by transmission, regardless of MDR status.

The figure below (Fig 3B in the paper) illustrates what we found:

What we see is clustering of a number of genotypes in the high-transmission area highlighted in the earlier maps, suggesting elevated rates of localized transmission within this area. We also see that cases of genotype 1, which is the most abundant genotype in the dataset with 134 cases (labeled 1 and highlighted in red in the figure above), are considerably more likely to be MDR within this area than outside of it, regardless of previous treatment status. This suggests that sustained transmission of MDR was occuring in this area during the study period, rather than being solely the result of spatially clustered treatment failure stemming from poor access to care, etc.

An important caveat to these findings, though, is that the fact that localized transmission seems to be driving this spatial clustering doesn’t mean that social risks underlying MDR acquistion from treatment failure don’t play a key role. It’s just outside of the scope of the modeling exercise here to close the loop between treatment failure and transmission. Doing that would require a finer (and even more expensive!) level of genotypic data. But the strength of the data we have here is the broad spatial coverage with still very detailed genotypic and drug-resistance data, which is essentially unprecedented for a dataset of this scale.